Advanced GMPL techniques 2: some handy tricks

Default values, display statements, derived parameters, etc.

- Prerequisites Advanced GMPL techniques: data/logic decoupling

In this lesson a few handy GMPL language features are presented, that can help a lot in making better models. None of these will help You to solve something, that you could not do before. These are just language features, that will make writing/understanding/debugging a model much easier. So keep in mind, that You are never "forced" to use any of these. If You don't feel the need to do so, then You probably shouldn't. These tricks are not there to make things more complicated, they are at Your disposal to make things simpler, if You feel they would help.

Later on we will use all of them occasionally, so You should be at least able to understand them even if You don't want to use them.

Default values for parameters

Suppose, that there is a model that You use with hundreds of data files, and there is a 0 dimensional parameter, e.g. tax rate, that has the same value in almost all of your data files, except for a select few. With the tools that we have learned so far You have two choices:

- Give the value for that parameter in all of the data files

- Create a separate model, where that data is fixed to a value, and use it for the majority of data files.

Option 1 is what seems obvious, but we feel that repeating that value so many times is not the nicest solution. Those data files share the same value for that parameter most probably, because they are bound to the same real life value. If that changes, we will have to change that in all of our models. Like the tax rate example mentioned above. If most of the data files belong to the same country, they use the same tax rate, but if the tax rate changes in the country, all the data files should be updated.

Option 2 is not better either. In this case, if the model constraints or variables change, we have to keep two of the models updated. Keeping them in sync is rather troublesome, and we also have to know, which model to use with which data file.

A nice solution would be to define a default value for that parameter, and

- if it is not given, it will take that default value

- if it is given in the data file, that default value will be overwritten by that one

The basic syntax is very simple: param Pname{...} default numericvalue;

Defaults can be useful in other situations as well. Imagine that You don't have hundreds of parameter files, but there is a 1 dimensional parameter, that is the same for most of the indices. An example could be an initial stock parameter, that is zero for most of the products, except for a few ones, when we are planning the production for a week. It would be nice just to give the values for those, and set all the others to 0 automatically. This type of default is useful, when the parameter in question has a "natural default value".

To achieve the aforementioned effect the model part should contain this:

set Products;

param initial_stock{Products} default 0;

And the data file could look like this:

set Products:= p1 p2 p3 p4 p5 p6 p7 p8 p9 p10;

param initial_stock:=

p3 100

p7 45

;

This works well with parameters having 2 dimensions as well. Suppose, that we want to schedule machines, and we have a parameter for the time a machine requires to perform a task, while having a number of tasks and machines. Not all of the machines are capable of carrying out all of the tasks, and we want to model that by giving a huge number for the processing time. The model part is pretty obvious:

set Tasks;

set Machines;

param processing_time{Tasks,Machines} default 1000;

But how do we define which values of a matrix we would like to give? Simply omitting the values would make the data section ambiguous, so we have to put a dot to the places where we don't want to give a value:

set Tasks := t1 t2 t3 t4 t5;

set Machines := m1 m2 m3;

param processing_time :

m1 m2 m3:=

t1 1 . 2

t2 3 . .

t3 1 2 3

t5 . 5 4

;

Note, that t4 is omitted from the list, so it is the same, as if we were to add a line with t4 . . ..

These magical dots and default values can be used for more complex situations as well, but we will be satisfied with using them only for this much (for now).

Transpose

A rookie mistake is to define a 2 dimensional parameter, and mix up its indices.

That usually results in "out of domain" error messages.

Replacing p[b,t] with p[t,b] everywhere where it was wrongly used in the constraints is a bit tiresome, but can be done swiftly.

A more serious headache will come around if we gave the values in the data section the other way around. That is especially true for huge tables. A small example:

set A;

set B;

param p{A,B};

...

data;

set A := a1 a2 a3 a4;

set B := b1 b2 b3;

param p :

a1 a2 a3 a4 :=

b1 12 34 54 12

b2 98 87 76 65

b3 78 65 67 43

;

The several options we have:

- Manually (or with an external tool) transpose the matrix in the data section.

- Change the order of the indices in the declaration, and everywhere in the model

- put

(tr)afterparam pand before the colon in the data section

Parameter safety checks

If we know that a certain parameter must always have a certain type of value, we should put that right after its declaration.

For example, the processing time above obviously can not be negative, so a declaration like param processing_time{Tasks,Machines}>=0; is better than the one above.

This doesn't really alter the logic, but we will receive an error message if by an accident an unrealistic value is given in one of the data files. So this is just a simple safety check for a simple mistake that could be made.

Measurement units

It has already be mentioned, that it is always a good practice to put measurement units in comments next to the declarations and definition to avoid catastrophe. However, it can happen that there is a parameter, that You often receive in one unit for some data files, and in another for other data files. You use one of them in your constraints, but You don't want to have separate model files for the two types of inputs.

A simple GMPL hack could be a solution for this, just consider the following declaration:

set Cities;

param distance_mile{Cities,Cities} >= 0, default 0;

param distance_km{c1 in Cities, c2 in Cities} >=0, default distance[c1,c2]*1.6;

And then use distance_km in all of the constraints.

Then in files using metric units You can give distance_km, and for files with imperial You can use distance_mile.

In the former, no conversion will be done, and the dot would mean 0*1.6 that is still 0.

In the latter, all the values for distance_km would be calculated based on the other values.

Just a bit of warning: if You don't give any of them, the distances will be 0 everywhere.

Displaying the results in a human friendly form

We have already seen in the generic model of the Fröccs example, that sometimes most of the variable take a "non-interesting" value in the optimal solution. In that particular example, the optimal solution meant producing 0 portions from almost all of the fröccs types, and there were only two, where this was not the case.

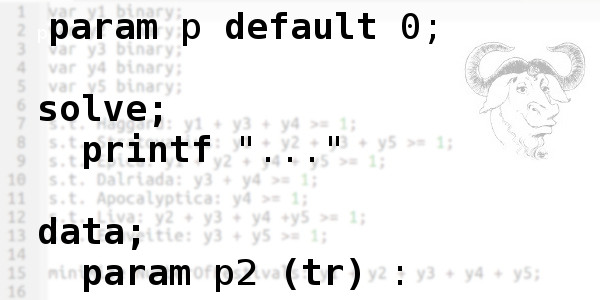

For industrial scale problems this can be even more drastic, having hundreds of variables, and only a several of them taking a non-zero value. It would be nice to somehow get a simple list of those variables and their values. Luckily, GMPL supports that, we can define a "display section" between the model and data section, where we can do something like this:

set FroccsTypes;

...

var quantity{FroccsTypes} >= 0;

...

maximize Income: sum {f in FroccsTypes} price[f]*quantity[f];

solve;

printf "Overall profit: %g\n\n", Income;

for{f in FroccsTypes : quantity[f]!=0}

{

printf "Produce %g portions from %s.\n",quantity[f],f;

}

data;

...

If we run the model with this, we will see something like this on the standard output:

Overall profit: 115625 Produce 937.5 portions from kisfroccs Produce 62.5 portions from soherfroccs

The first important thing is to start this section with the solve; keyword, that will notify the solver, that the model description has ended, and it should solve the model before progressing further.

This ensures that in this display section, the "variables" are no longer variables, they have values, the values that they hold in the optimal solution.

printf is a commonly used command for formatted output.

If You have some background in C, bash, etc. this syntax will not surprise You.

If not, I highly recommend studying the printf syntax.

To get the basics understood: the first string after printf is what the command should output.

If that string has a percentage symbol and then something, that special marker will be replaced by the next thing listed.

%s is used to output strings, %d for decimals, and use %g for non-decimals.

printf is pretty powerful, so again, I highly recommend using the documentation, but what we have in the above example already lets us to do nice things.

The other thing is the for structure, that is a foreach type of loop.

It basically goes through all of the fröccs types with a dummy index.

After the colon, we can put filters, in this case we want to express that we go only through those fröccs types, that are actually produced in some quantity.

sum too, but only with parameters.

As opposed to the display section, the variables do not have a fixed value in the model section.

The for loop above is equivalent to something like this:

for {f in FroccsTypes}

{

if {quantity[f]!=0}

{

printf "....

}

}

Now it was simpler to just have a filter, however, sometimes we really need an if conditional.

Unfortunately, there is no such element in GMPL, but there is an ugly hack with loops:

for { {0}: quantity[f]!=0}

{

....

}

This basically goes through all of the elements of the set \(\{0\}\), and checks the condition for all of them.

Obviously the set has nothing to do with the condition, and any singleton set would do.

Definitely not nice, but it works.

Output as input for a subsequent tool

The formatted output above is nice for us, humans to read. Sometimes, however, we want another software tool to further use the data that we gain from the optimal solution. A simple example is to generate a table, that can be coied to Excel or any other spreadsheet software. This can be done for example by separating all the outputted values by tabulators, and then just copy-paste the output from the terminal to that software.

Copying huge tables from the terminal can be rather painful, and it makes easy to do mistakes.

Not to mention, that the output is mixed up between the standard log messages of the solver.

It would be nice to redirect our specialized outputs to a separate file.

This is exactly what the -y command line option is for.

Just run glpsol -m model.mod -d data.dat -y myoutput.txt, and then You will have everything "copypasted" to that file.

So, if You plan this output to be used by Excel, create a CSV file from these statements.

- The mentioned CSV format for Libreoffice Calc with various data

- Tables in LaTeX are a bit cumbersome, so I generated the LaTeX table code immediately.

- To better visualize a solution, I have generated an SVG image file.

glpsol from a script, that calls then the script generated from the display statement, etc.